Stunting: A Silent Emergency

An estimated 151m children under five – one in four children worldwide – become ‘stunted’ through poor nutrition. It is not just a matter of height. It leaves them cognitively impaired for life.

An estimated 151m children under five – one in four children worldwide – become ‘stunted’ through poor nutrition. It is not just a matter of height. It leaves them cognitively impaired for life.

The hair on her temples is damp with sweat, and her eyes are closed.

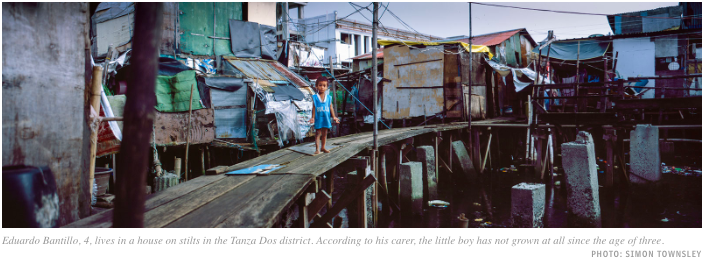

Maryann Barrios is sick, again, and asleep in her mother’s arms in the shade of a tarpaulin outside their one-room shack in Manila, capital of the Philippines.

Maryann is only two, but she has been in and out of hospital every month of her short life, because she is severely malnourished. Behind her, her five-month-old baby sister coughs and a thin white worm emerges out of her mouth and falls onto the muddy floor below. None of the women or children surrounding her give it a second glance.

“It’s a hard life,” says their mother, Mylene Barrios, 34. She estimates the family get enough to eat just two days in every week. All get worms regularly, and Maryann was in hospital last week because of severe diarrhea that left her, as her mother says, “skin and bones”. She barely looks healthier now.

Their home, part of an illegal settlement near the docks in the Navotas City area of Metro Manila, is metres from foul-smelling black flood water that rises whenever it rains, piles of rubbish, and a fruit seller vainly batting away flies from her wares, displayed on an old pool table.

Maryann is severely stunted and wasted – meaning she is both too short for her age and too thin for her height. She weighs just 7kg, and is 76cm tall. That is 10cm and 4.5kg less than the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests she should measure, based on its global growth charts.

Maryann is not unusual in the Philippines. In fact, one in three children in the country have stunted growth – and in some areas, it is one in two. According to data from Save The Children, it is the ninth worst country in the world for stunting.

“This is a silent emergency,” says Dr Amado Parawan, Save The Children’s nutrition advisor in the Philippines. “And we have to get our act together. The children deserve better.”

Mylene, who has four children, knows this, and it torments her. Her husband works as a tricycle driver and makes 200 Philippine pesos on a good day (less than £3). It is not enough. “I cry that I don’t have enough for my children,” she says. “I just want them to have an easier life.”

Sadly, their difficult start makes that unlikely. Stunting does not just mean that children are small for their age; it has lifelong physical and mental consequences that are largely irreversible. According to the WHO, the condition covers stunted growth, development, and a lack of opportunities for play and learning. It is seen as one of the most important indicators of children’s health; effectively, the opposite of wellbeing.

The problem is huge: there are 151 million stunted children under five years old globally. Astonishingly, that is almost one in four. Malnutrition remains the cause of almost half of all deaths for under-fives.

In the short-term, being stunted means a child is more likely to get, and then five times more likely to die of, diarrhoea. And it is a vicious cycle. Just five episodes of diarrhoea before a child’s second birthday can lead to stunting.

The long-term picture is even more devastating. A stunted child’s brain development is so profoundly affected by the lack of nutrients that they are likely to be cognitively impaired for life, earning on average 20 per cent less than their non-stunted peers. Children who are deficient in iodine, just one of the nutrients necessary for growth and development, can lose up to 13 points from their IQ. Their immune systems are weakened, life expectancy is lower, and they are at greater risk of diseases like diabetes and some cancers in later life. Ironically, they are also at risk of obesity and being overweight later in life, too. Plus, it is intergenerational: a malnourished mother is likely to give birth to a malnourished baby.

“Their lives will be harder,” says Dr Parawan shortly.

His team at Save The Children work with children like Maryann in Manila’s poorest areas, providing feeding programmes, nutrition advice and ready-to-use-therapeutic foods. The charity will start a cash transfer programme soon in a bid to change behaviours while providing nutrition.

“In a year, we lost 328bn Philippine pesos (£4.7bn) due to stunting – that’s nearly 3 per cent of the GDP of the Philippines,” Dr Parawan says. “The children get sick, it affects their education, it costs them in terms of getting a job. So it really affects the future of the country.”

And in the Philippines, despite a growing economy, stunting is getting worse. In 2013, 30.5 per cent of children were stunted, according to the National Nutrition Survey. By 2015, it was 33.4 per cent.

Dr Parawan says the increase is probably because the country’s mounting wealth has not reached its poorest, where families are trapped in an intergenerational cycle of malnutrition. Plus, historically there has been a lack of focused action from the government.

That could be about to change: last month, the Philippines controversial president, Rodrigo Duterte, added malnutrition to his to-do list. “Just like [the] drug abuse that has permeated our society, malnutrition has to be stopped now!” he said.

Duterte’s drug wars have seen thousands of horrifying extrajudicial killings take place across the country. But while the strategy has been condemned internationally, no-one could accuse Duterte of inaction on drug abuse.

Perhaps now it is malnutrition’s turn. In July, the president signed a national feeding programme into law.

We witness a local version in a district close to Maryann’s in Navotas City. Based on the basketball court-like top floor of the local health center of North Bay Boulevard North, the feeding programme has rice, pork and quail egg on the menu. It is free, and popular – too popular. Around 30 children are there with their parents. The food runs out ten minutes before the event is even supposed to begin.

Last year, the government also drew up a new nutrition strategy, the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition 2017-2022. It aims to reduce stunting to 20 per cent in the next five years.

When asked about the budget for the plan, the National Nutrition Council is unclear, but as an opening gambit pointed to a PHP 269m (£3.9m) pilot programme this year that has reached 12 of the 81 provinces of the Philippines, involving nutrition classes, some food supplementation, national adverts and the distribution of weighing scales and measures.

It might not sound like much, but it is a positive step. However, there need to be many steps taken together in order to tackle stunting, says Dr Francesco Branca, the WHO’s director of nutrition.

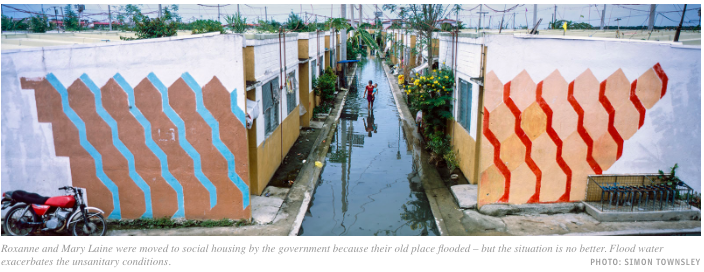

For example, Maryann does not have enough food; but even if she did, the unsanitary conditions she lives in could still lead to repeated infection, which would put her at risk.

The lack of food, described technically as inadequate infant and young child feeding practices (including a lack of breastfeeding), alongside infection, are listed by the WHO as two of the main causes of stunting. Given Maryann’s family’s poverty, she has probably also been affected by the third: poor maternal health and nutrition.

“Stunting is a genuinely multisectoral issue,” says Dr Branca.

“Like in the Philippines, the lack of clean water and sanitation facilities is a major reason for things not moving that quickly. Clearly we are often in a circumstance where the ideal environment for the growth of children is not guaranteed.”

But Dr Branca says the urgency to act cannot be underestimated. “We’ve been very active on the environment because we are under pressure because of the collapse of the planet. But malnutrition is a similar collapse. We need to act,” he says.

There is a key reason for action. For every two years that passes, there is another lost generation. This is because the key time for preventing stunting and laying the right foundations for a child’s healthy development for the rest of their lives is in the first 1,000 days: from conception to their second birthday.

Adrianna Logalbo is the managing director of a leading nutrition advocacy organisation called 1,000 days. She says the concept of this window was “ignited” by evidence put forward in The Lancet in 2008.

“It really showed how critical nutrition for pregnant women, babies and toddlers is, and that evidence has only continued to grow,” she says. “I wouldn’t say all is lost when a child turns two, but it does make it harder.”

The Lancet series proved what seems obvious: the reason why nutrition is so critical in these early years is because the pace of growth then is so rapid. And it is not just physical. Cognitive function is also developing, and is dramatically affected by a lack of nutrients. Studies have shown that undernourished children’s brains do not form in the same way as those who get adequate nourishment.

“If only we could invest to prevent,” says Ms Logalbo. “We are trying to make the case, but part of the problem we face is that mums and babies simply haven’t been a priority.”

That is certainly the impression that you get in the slums of Manila, where Dr Parawan’s description of a silent emergency really hits home – and highlights why the world has been slow to wake up to what academics have described as the “hidden scourge” of stunting.

Children roam around in vests, grinning and grabbing food where they can, and at first glance you can’t tell how malnourished or stunted they might be. But when we ask Save The Children staff how many of the children in, for example, Maryann’s area are affected, the answer is simple. All of them.

Sometimes the problems are more heartbreakingly obvious. In Bangkulasi district in Navotas, Marc Anthony Fernandes Riego, two, is not roaming around. He lies still, looking like a child caught up in a famine. He stares blankly out of his large, dark eyes while his mother, Aurora, 45, speaks.

Marc weighs 4kg – just under 9 pounds, a weight that would be considered a healthy newborn in the UK – and is 77cm tall.

He was born underweight, and Aurora admits that she did not have enough to eat while she was pregnant. She also did not have access to a health visitor, because she stayed in her home province in the countryside while pregnant.

“I blame myself for what has happened to Marc,” she says. “I ask myself, why did this happen to my child? He is the only one who has been born like this.”

Marc was almost certainly already stunted when he was born. This is the case for a lot of children: a study in Malawi found that 20 per cent of stunting begins in utero.

Marc also has a number of other health conditions, from an enlarged heart to development delays. He cannot walk or speak. He is breastfed, but struggles to eat other foods, which the local health worker says is linked to his other conditions.

Aurora has taken him to hospital for help, but she can’t afford the ongoing therapy or operations. She has nine other children, five of whom still live with her and her husband in their small, stone room off a narrow motorcycle alley.

“It’s tragic, but so common [for Aurora to blame herself],” Ms Logalbo says. “But it’s hard as an individual to appreciate that the system we are living in is throwing up one barrier after another to our health. There were a whole host of systems that failed that child, the least of which is his mother trying to do everything she can in constrained circumstances.”

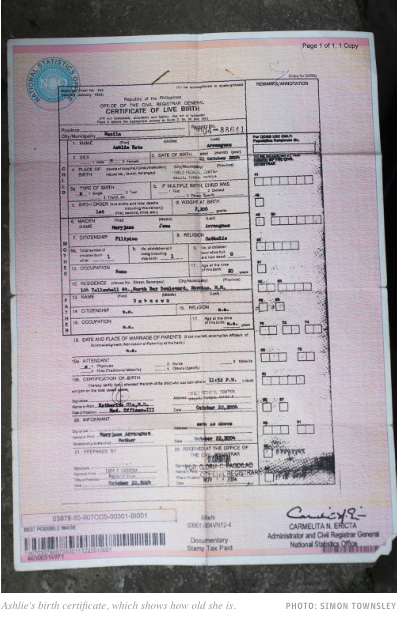

The same is true of Ashlie Arangues and her family, who live in North Bay Boulevard South in Navotas. While most of the children we meet are in that crucial 1,000 days window, Ashlie is not, and she is an example of what happens when that window slams shut.

At first glance, she seems about 6 years old. She is 13. “My friends are all taller than me. I am the smallest,” she says. “It’s fine.”

But behind her pre-teen bravado, Ashlie knows it is not fine. Her mother died of malnutrition related causes two years ago, and she and her three siblings live with their granddad, Danilo, 62. They are homeless, staying with relatives, and Danilo can’t work, because he has TB. As such, they barely eat.

“It’s a struggle,” her grandfather says. “Sometimes I just want to give up.”

Ashlie is currently off school, partly because the teacher told her not to come because she has missed so much, and partly because she can’t afford food when she is there. This, too, is common: research has shown that children who are stunted aged two go on to complete one full year less at school on average.

Ashlie’s height and weight have not been officially recorded because she is too old for any of the health intervention programmes, which focus on the crucial first 1,000 days, but I measure her at around 3 feet tall, or 91cm. I can’t check her weight, but she is tiny, with limbs like twigs.

She is a cheerful soul, but desperate. Neither she nor Danilo can remember when they last had enough to eat.

“The maximum we eat is two times a day. It’s worse when it’s only once,” she says.

“I get stomach pains when I am hungry, and headaches. I sometimes stop playing when I think I can get food. Most of the time I am so tired.”

Her smile falters a little. She wants to be a nurse, but they both know her chances are slim, and fading every day she does not get enough to eat or go to school.

“I have confessed to my friends that sometimes I cry,” she says. “I don’t know what will happen in the future.”

Ashlie, like Marc Anthony and the other children we meet, is the human face of the hard to grasp numbers already discussed.

The fact is that stunting remains stubbornly common despite ten years of action following The Lancet’s series and an increased global focus on nutrition.

Stunting is in decline – it has gone down by 41 per cent since 1990, when there were 257m stunted children – but experts agree it is not going fast enough, as 2018’s Global Nutrition Report is set to show when it is released later this year.

The WHO wants to reduce stunting by another 40 per cent by 2025, meaning there would only be around 100 million affected under-5s by then. At the moment, it is going to miss its target by 14 per cent - or, in real terms, 27 million children.

Alongside the WHO, the major agencies of the world are focusing on nutrition. Zero hunger is one of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, to be delivered by 2030. Initiatives like the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement (SUN), a network of member countries organised by the UN and funded by charities and some Western governments, is a best practice guide.

The UN kicked off what it calls a decade of action on nutrition in 2016, focusing on implementing programmes to address the issue across member states. But the problem is a lack of investment at the country-level, says the WHO’s Dr Branca.

“We get frustrated because it is actually in the interests of countries to act,” says Dr Branca. “For every dollar invested in nutrition you get at least a $17 gain. What else do you need?”

Moreover, he says, there are clear examples of success. He points to Ethiopia, where recent action to make healthcare more accessible simply by boosting the numbers of health centres and workers is making a rapid difference. Stunting has decreased by 4 per cent since 2010.

Or in Brazil, the incidence of stunting was reduced from 55 per cent in the north-east of the country in the 1970s to just 6 per cent by 2006. The remarkable results came from a coordinated effort including the launch of a national healthcare service and the country’s income transfer system, where families below the poverty line get a monthly stipend.

There is a lot of scope for improvement, Dr Branca says. Even in the field of immediate intervention for severely malnourished children, evidence suggests that only one child in 10 currently has access to quality services.

“This is a great opportunity to act. For the first time we see a global awareness about this, that something can happen,” says Dr Branca.

And while the situation is serious, he is adamant that examples like Brazil show that stunting can end within our lifetimes, if the political will – and the money – is there.

“I remember when we started tackling this. People were sceptical, they said we’d need at least two or three generations. You hear different language now,” he says.

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Words by Jennifer Rigby. Photographs by Simon Townsley

Source: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/stunting-a-silent-emergency/