To keep patients safe in hospitals, the accreditation system needs an overhaul

Once a year, inspectors visit hospitals across the country to assess their performance on a range of measures,

Once a year, inspectors visit hospitals across the country to assess their performance on a range of measures,

from medication safety to consumer engagement. But it’s not a secret shopper-type scenario. Hospital staff have known for months when the inspectors will arrive and what they will be looking for.

It’s no wonder doctors dismiss the process as irrelevant or a waste of their time. But most concerning is the process doesn’t identify the key safety issues in hospitals, nor propose ways to address them.

Almost every significant safety failure in Australian hospitals in recent decades has happened in a hospital that had passed accreditation with flying colours.

Bundaberg Hospital passed accreditation, despite allowing surgeon Jayant Patel (later dubbed Dr Death) to continue practising after complaints from patients and staff about his competence.

Bacchus Marsh Hospital, where seven seven babies died after receiving sub-optimal care, had regularly passed accreditation. The hospital was about to get a new accreditation certificate when the story broke.

And Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital in New South Wales, where a gas mix-up left one baby dead and another brain-damaged, was accredited.

A new Grattan Institute report shows how accreditation needs to change. Australia’s one-size-fits-all system of assessing hospitals against centrally determined “standards” must be replaced with a system tailored to address the specific weaknesses of each hospital.

The report shows that a hospital’s performance in one specialty is unrelated to it’s performance in another – a hospital may have the lowest rate of surgical complications in orthopaedics, but the highest rate of medication complications in general medicine.

One size fits all system

Some 40 years ago, I evaluated Australia’s relatively new hospital accreditation system for my PhD. Back then, hospitals were expected to meet a set of standards. Inspectors visited a hospital to assess it against the standards. They produced a report, which remained secret.

An independent body would make an assessment of the report, and the assessment also remained secret. Then, in almost every case, the hospital was awarded “accreditation”.

Inexcusably, today the process remains the same (though we do have better standards and a better report). No other part of Australia’s hospital system has been so immune from fundamental change over those 40 years.

Back then it was difficult to measure a hospital’s performance on patient complications, and the quality of care. This was partly because we didn’t know whether a patient had a particular diagnosis when they were admitted to the hospital, or whether the diagnosis arose because of something that happened in hospital.

We couldn’t compare one hospital with another hospital, so we had to rely on independent qualitative judgements.

Not any more. Today we can measure hospital complication rates and other safety indicators to assess a hospital’s performance and compare them with others.

The dangers of a one-size-fits-all accreditation system can be illustrated by considering infection control, which is one of the current national standards for hospitals.

Hospital-acquired infections are widespread – more than one in every hundred patients contract one – and cost the hospital system almost A$1 billion each year.

The accreditation visit to the hospital with Australia’s lowest hospital-acquired infection rate will look very similar to the visit to the hospital with the highest rate. The same information will be read, people in the same roles will be interviewed, and the same boxes about identifying the problems and training staff will be ticked.

But the hospital with the worse infection record will have no way of learning from the best performer, and infection rates across the system will be unlikely to improve.

Tailoring accreditation

A new accreditation system needs to be tailored to each hospital’s situation.

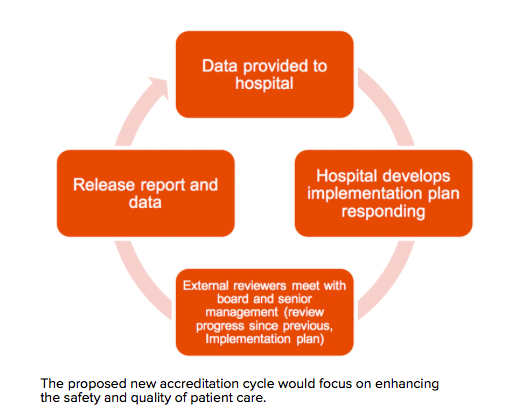

All hospitals – public and private – should be given data about their complication rates and how they compare to other hospitals. The data provided to each hospital should be so specific that the hospital’s orthopaedic unit, for example, can compare its complication rates with its peers.

Hospitals and their clinical units should then develop plans to reduce their complications rates:

Under the plan, hospitals would no longer be spruced up for a scheduled, visit by accreditation inspectors every few years. Instead, surveyors would visit without notice. The surveyors would focus on providing feedback to the hospital on how it can strengthen its own safety processes.

After each visit, the survey report should be released publicly. That way, patients and their families and GPs could make better-informed decisions about which hospitals to go to.

The cycle of visit and report should be repeated every few years.

This dramatic change to the way Australia’s hospitals are accredited cannot occur overnight. Data has to be provided to hospitals in an actionable form, staff have to be trained in how to understand statistical variation and how to implement improvement strategies, and the new model needs to be piloted and evaluated.

But the sooner we make the transition, the better we’ll be able to care for Australians who have to go into hospital.

By: Stephen Duckett